Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In the United States, and increasingly around the world, the phrase “climate change” is quietly disappearing from political speech. A recent poll by the Searchlight Institute, a Democratic think tank, found that while most Americans agree global warming is a serious problem, very few see it as a personal or immediate concern. The result: politicians are now rebranding climate action as “cheap energy” or “energy affordability.”

This shift in language marks a dramatic evolution in how climate policy is being communicated, and it could reshape public engagement with the clean energy transition.

The Searchlight Institute’s latest poll, The First Rule About Solving Climate Change: Don’t Say Climate Change, surveyed more than 1,400 voters across seven U.S. battleground states. The results were clear: while voters overwhelmingly support clean energy and pollution reduction, mentioning “climate change” itself immediately polarizes opinion.

When politicians use the term, support among Republicans drops sharply, creating a 50-point partisan gap. Even among independents, the phrase evokes “suspicion” rather than motivation. Searchlight’s advice to policymakers was blunt; talk about affordability, not the atmosphere.

Source: Searchlight Institute, “The First Rule About Solving Climate Change” (2025).

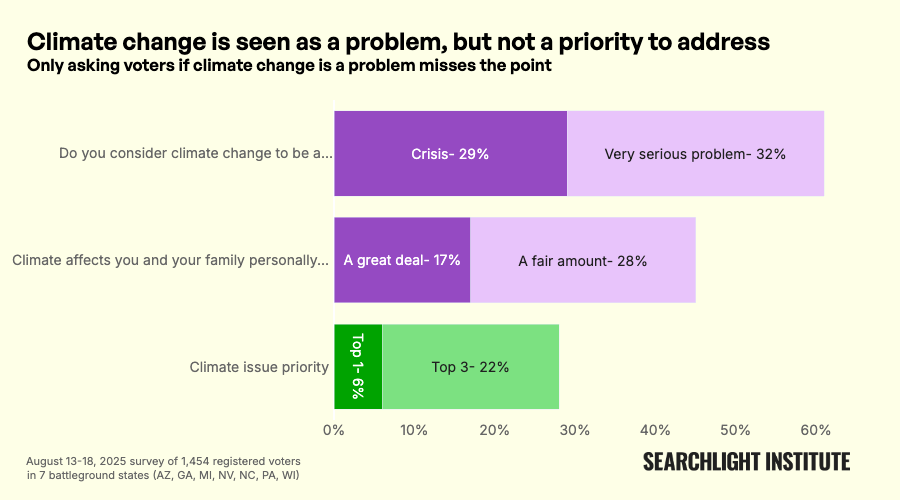

While 61 percent of voters said climate change is a serious problem, only six percent listed it as a top issue. By contrast, 71 percent said affordable prices were their highest priority, followed by healthcare and jobs.

Voters may care about climate change in principle, but a few feel it affects them personally. Only 17 percent said it impacts their own families “a great deal.” The result is a psychological disconnect. People recognize the crisis but view it as distant, abstract, and someone else’s problem.

Here lies the Democrats’ core challenge. Nearly half of voters (46 percent) think the Democratic Party’s top priority is climate change, even though it barely registers in their own. Meanwhile, they see Republicans as more focused on affordability and jobs, even if those priorities come with weaker climate credentials.

This mismatch is eroding political traction. As Searchlight’s report warns, “Voters are looking for immediate help with rising costs rather than solutions to abstract problems.”

In political communication, certain words carry emotional baggage. “Climate change” has become one of them. Searchlight found that many voters associate the term with political posturing, elitism, and moral lecturing.

By contrast, words like “lower bills,” “cleaner air,” and “energy independence” produce bipartisan agreement. The irony is that these goals often come from the very same climate policies that politicians hesitate to name.

There’s a catch. Simply adding “affordability” to a climate message doesn’t make it work. Voters can tell when the cost narrative is an afterthought. As the report puts it, “Voters can tell when affordability is an afterthought, and it doesn’t neutralize the toxicity of the term ‘climate.’”

To win trust, policies must demonstrate real and immediate cost benefits, not distant promises of savings from electric vehicles or efficiency upgrades. The energy transition, in voters’ eyes, must first show up as a smaller utility bill.

That brings us to the most striking statistic in the report: 63 percent of Americans say utility bills are the top strain on their household budgets, ranking even above food and housing costs.

This economic pain is the emotional gateway for climate policy. Renewable energy offers a genuine solution by reducing fuel price exposure and stabilizing electricity markets. As shown by a separate Nature Energy study from Cambridge and Harvard, accelerating solar and wind deployment could reduce Europe’s power price sensitivity to natural gas by 65 percent. The same logic applies globally: clean energy isn’t just green, it’s economically defensive.

From Washington to Canberra to New Delhi, governments are learning that public support grows when climate policy is framed as economic progress. “Cheap, clean energy” sells better than “carbon mitigation.”

But this linguistic shift carries a warning. If politicians stop talking about climate altogether, the urgency behind the issue could fade and with it, the moral clarity that built today’s clean energy movement.

The smartest leaders will strike a balance: making climate policy sound like economic policy without erasing the reason it matters. Because if we stop saying “climate change” entirely, we might win the narrative but lose the fight.