Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

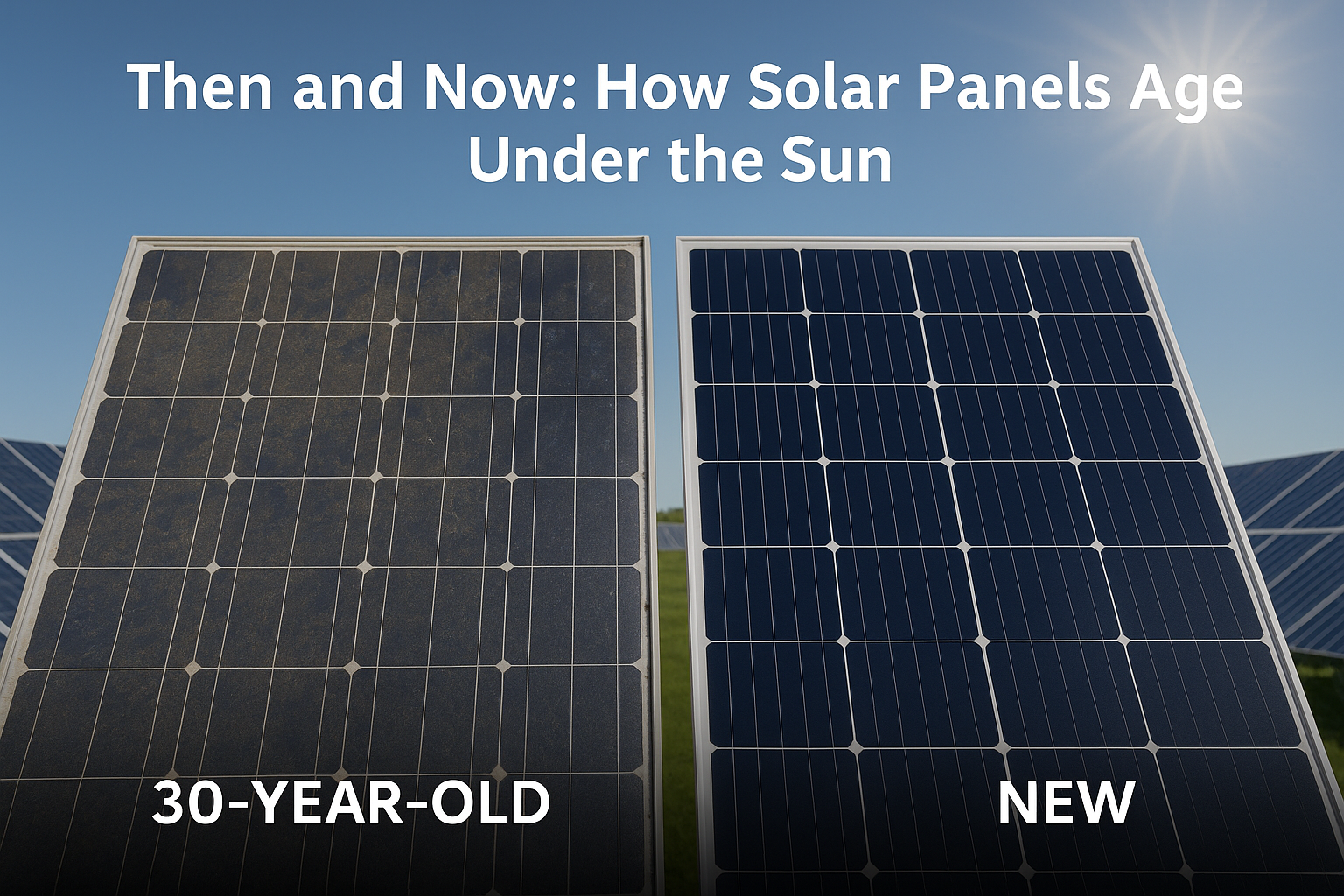

After 30 years under the sun, some of the world’s oldest solar panels are still producing power — and valuable insights. A new long-term study reveals how these panels aged, what materials lasted the test of time, and how this research could redefine the future of clean energy design and durability.

When the first generation of solar panels was installed in the early 1990s, few expected them to still be producing electricity three decades later. Yet, a new long-term study on 30 year old solar panels from Switzerland has revealed that some of those early modules are not only functional but also shedding light on how photovoltaic (PV) technology can be made more durable, efficient, and sustainable in the decades ahead.

The research offers a rare glimpse into what truly happens to solar panels after 30 years of exposure to sunlight, temperature fluctuations, and environmental stress and the findings carry an important message for the entire PV industry.

The study, led by a Swiss research consortium, examined a collection of solar panels installed more than 30 years ago that are still producing electricity. These early “suncatchers,” as one researcher described them, were made with materials and processes that now seem primitive compared to today’s advanced module designs.

However, the panels’ endurance surprised even the experts. Many continued to operate at 80–90% of their original efficiency, despite years of thermal cycling, UV radiation, and mechanical stress. The study also found that the type of encapsulant, backsheet, and soldering method had a measurable influence on how well each module aged.

“Everything that goes into a panel has a great influence on performance,” one of the researchers said. “By understanding which materials degrade fastest and which resist aging, we can design panels that last far longer than their warranties.”

Solar panels degrade primarily due to slow chemical and mechanical changes inside their layered structures. Over time, UV light, humidity, and temperature fluctuations can cause the encapsulant (the polymer that seals and protects the silicon cells) to yellow or delaminate. Tiny cracks in the solder joints can also form, increasing electrical resistance and slightly reducing output.

However, what this long-term study revealed is that degradation in these 30 year old solar panel is not linear. Most panels lose performance faster in the first few years, then stabilize for decades. That means the typical “0.5% per year” degradation assumption used in warranties might actually underestimate the real-world durability of well-built modules.

Another surprising finding was that environmental factors matter more than age alone. Panels exposed to consistent but mild sunlight like those in central Europe tend to last longer than those under extreme heat or dust conditions. This highlights how local climate, installation angle, and even mounting hardware can affect long-term stability.

For decades, 25 years has been the industry benchmark for a solar panel’s “expected lifetime.” But this study challenges that assumption. Many of the Swiss panels, now entering their fourth decade, continue to perform at levels that make them economically viable.

If manufacturers can extend lifetimes from 25 years to 40 or more without major cost increases, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar could drop significantly. That would make PV not just the cheapest source of new electricity, but also one of the most long-lasting energy technologies ever developed.

Manufacturers such as LONGi, First Solar, and Canadian Solar are already incorporating durability research into their next-generation designs, experimenting with new glass coatings, UV-resistant polymers, and recyclable encapsulants. The goal is clear: build solar modules that can withstand decades of harsh environmental exposure without losing performance or structural integrity.

For homeowners, these results bring welcome news. The panels on your roof aren’t likely to “die” when their warranty expires. They just produce slightly less electricity each year. High-quality systems can continue generating meaningful output for 30–40 years, especially if installed with durable mounting structures and regularly maintained.

Investors and utilities are also taking note. As solar farms reach maturity, the prospect of repowering rather than replacing panels becomes more attractive. By swapping out degraded modules selectively while keeping existing infrastructure, operators can extend project lifetimes with minimal additional cost or waste.

This also supports the rise of circular economy practices in solar manufacturing. If panels can last twice as long, the environmental footprint per kilowatt-hour falls dramatically, reinforcing the idea that durability is the new sustainability.

What these 30-year-old solar panels prove is that longevity is not just possible, it’s measurable, repeatable, and improvable. Every old module that researchers take apart helps them identify how materials, soldering techniques, and encapsulant choices impact long-term resilience.

The next generation of panels may one day last 50 years or more, with power electronics and mounting systems designed for easy replacement and recycling. Coupled with modern bifacial and perovskite tandem technologies, the solar systems of the 2050s could deliver more power per square meter and operate almost maintenance-free for half a century.

As the researchers concluded, “We can learn from these old panels to make future ones last, hopefully, as long.

This study carries an important message for the PV industry: the future of solar energy isn’t just about improving efficiency, it’s about mastering endurance.

By learning from the past, manufacturers and scientists are discovering how to design panels that last longer, perform better, and generate cleaner energy with minimal waste. Every decade of real-world performance data strengthens the case for solar as the most reliable, scalable, and future-proof power source humanity has ever built.

In other words, the sun’s oldest students are still teaching us how to get better at catching its light.

Source: “Three decades, three climates: environmental and material impacts on the long-term reliability of photovoltaic modules” 2025, https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2025/el/d4el00040d

Leave a Reply